Hofmann Family History, Part II

Part II: From Schernau to Zell, early 1900s to 1930

Schernau was owned by a noble family, the von Romans. They were French Huguenots,

Protestants, who were expelled from France for religious reasons after a horrendous and

protracted political struggle. These Protestants brought skills and money to their new homelands and for these reasons were generally accepted by local German rulers, whose lands were in need of development. The von Romans bought the village, which is near Kitzingen, a town where American soldiers had some barracks for many decades after WWII. Everyone in Schernau was Protestant because their owners were Protestant. Most of Bavaria was - and remains - quite Catholic. The von Romans

have a website, and you can see the

whole long lineage presented there. I have been to the graveyard in Schernau, where the remains of the Hofmanns and the Bischoffs, Uncle Killian's family, are all still present, along with their noble overlords, though the tombstones and crypts of the von Roman's are larger. Schernau's situation as a Protestant village was not unusual for the time. Though most of

Bavaria is Catholic, it was checkered with islands of Protestantism, sometimes whole cities, like Nuernberg, who

were not willing to obey the Church, and were strong enough to assert their independence, the main reason being that it was better for them economically not to have to be sub-servient to the Church. Religious prejudice was quite strong, both sides not really liking each other in daily life. As time went on, however, this lessened, but not to the degree that intermarriage was common.

To give an idea of what times were like around the turn of the century (1900), there is a story I heard my father tell about himself in Schernau: apparently as an infant, he was

very sick at one point. There was not much around in the way of medical care in Schernau, where he

was born in 1899, so they called in a Gesundbeterin, a woman who prays over the sick. My

grandfather left to go to work, took a look at the infant, and told my grandmother, Wilhelmine,

that he would be dead when he returned. He lived, since I am here to tell about it, and you to

hear.

As far as I know, Schernau is still rural, though there are new houses there and at least one home

for old men, one that takes all comers, regardless of background, homeless men, too. I went

there twice, both times at my request. The first time was in 1969. My parents were in Germany.

They had bought a new Volkswagen and so had I at the time, and we drove from Zell to

Schernau for some reason in two cars. The ancestral home was pointed out to me. It was all still

very rural, the road unpaved, chickens running around, very much the Dorf, or hamlet. There were two old ladies in a yard, one of them

talking about aging and getting older, being unwell at times, about being so sick she thought it

was the end, and talking about ‘going over’ in her delirium. Another man, leaning on a cane, not

very tall, came walking down the street. He took one look at my father from ten feet away, and said "Ah, well, there

he is, the American!" They had not seen each other in many decades, all of WW II had transpired in the interim, but still recognized each

other. We had Kaffee that afternoon at Philip Bischoff's house with some of his relatives. The

second time was in 1989, when Margit Grigat drove me up from Fuerth. We drove up the

Autobahn at excessive speed, and spent an hour or so there. It was on that visit that I explored the

graveyard, which is fairly large, and like most German cemeteries, quite well tended. The village

had changed by that point. The roads were paved and some of the houses were homes for U.S.

Army personnel from nearby Kitzingen. I think it must now be a place where Germans and

others have their retirements, since the troops are no longer likely in Kitzingen. There are still

extensive fields around the town.

There was a general movement towards cities in the late 1800's and early 1900's for excess

population, just as there is today in many parts of the world. My grandfather, whose first name

was Sebastian, apparently headed over to Wuerzburg and to Zell, where he

became a factotum of some sort in a brewery, Bürgerbräu. He cleaned up the place and took care of things, a

janitor and handyman. They had three children, my father, Tante Rosa, whom you might have

heard mentioned, and Nicholas, Nicklaus (my middle name).

Nicklaus Hofmann fell in WW I

My father, Georg, was apprenticed at 14 to a baker in Nuernberg, about 100 kilometers south of

Wuerzburg. Up in the middle of the night, off to work, getting bossed around by everyone at the

bakery and doing a lot of hard work. This was not what he wanted to do. It was his father’s

choice. The old man, who looked in the few pictures that I have seen of him, like a study out of

August Sander’s portraits of Germans during the Weimar period, hard faced, beady-eyed and

work-worn, had the notion of opening a restaurant, probably a beer parlor, and had the notion

that an adjoining bakery would be just the ticket. My father had his sights set on having a career

with the industry that had its plant across from Zell, one that produced first rate lithography

machines which were sold all over the world. He wanted some sort of modern, technical career.

He had a good head for figures. He liked music. He was an extra at times in the opera house in

Nuernberg. Just the right age for cannon fodder for WWI, he was yanked into the German army

and sent to France, where he was wounded. His brother, Nicklaus, had already fallen in the War in France. My father recuperated in Germany (George thinks France)

for a year and then was stationed briefly in Berlin before he was sent to be a guard somewhere in Italy. I recall him telling me all this at some point. He also warned me that if I was ever in a war, not to aim high and shoot into the air, not at the other men.

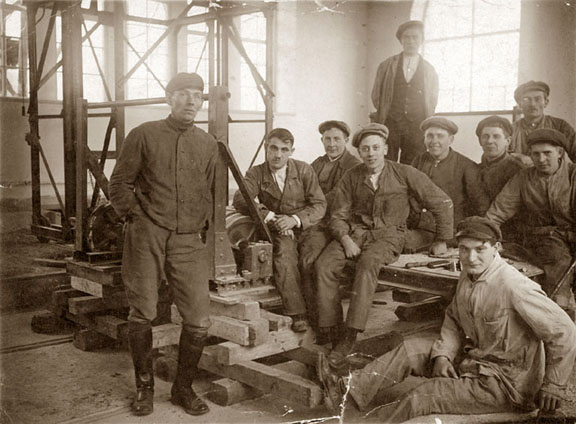

From boy to soldier boy...

...to a hospital in Germany or France

My father is seated fourth from left. I saw scars on my father's arms and one of his legs, but he seemed to have no lasting physical effect from his wounds. The young man at the right end of the table is missing a leg.

In the post-WWI period at some point in the 1920's, my father, Georg Hofmann, was a part of a work corps in Bavaria (southern Germany) stringing up electrical lines. Electrification was just getting started in those days in Germany as well as the U.S.

Georg Hofmann is fifth from left

Georg Hofmann, seated center rear

Options:

Return to the top of page Part II: Schernau, Zell, WW I

or proceed to Part III: Emigration to U.S.

or proceed to Part IV: Margarete Vogl

or return to Part I: Reaching Back, Zell am Main

or return to Index